Fashion Book Friday: Men in Black by John Harvey

This is my archive of fashion related books. Most of them are in English, but many are not. Some are new, but many are real finds. Depends on the topic, really...Here is another find from Brazil, so, while it was originally written in English, my edition is in Portuguese.

Menswear usually takes a backseat in fashion studies, and rarely makes it out of the general introductory type of book. Which makes this little gem all the more special.

It is almost entirely dedicated to menswear, to the preponderance of black in male clothing, to be

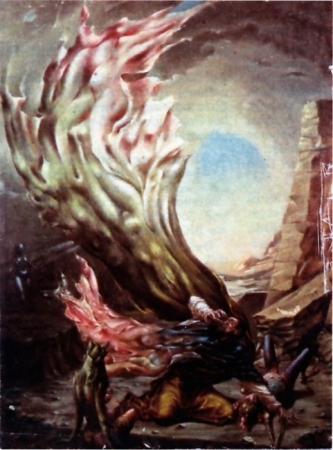

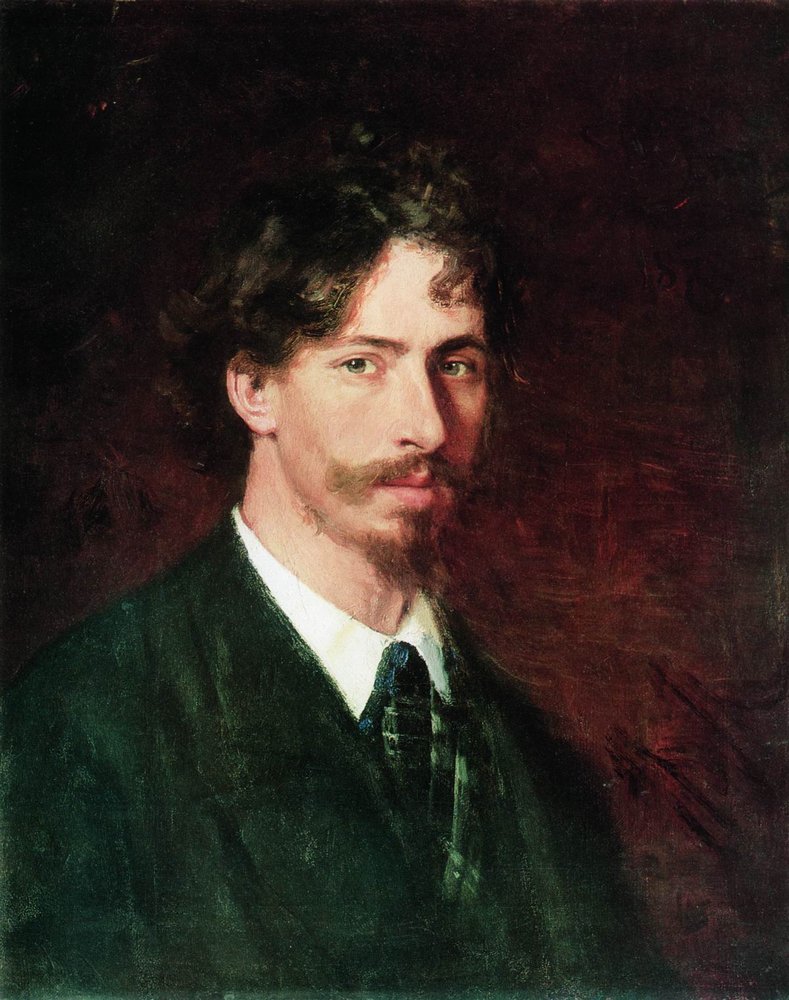

John Harvey looks at how the nineteenth-century gentleman dresses himself almost entirely in black, at a time whe women prefer strong or bright colours (such as in this scene by Renoir) and follows the "biography" of Black since the Middle Ages (when it meant renouncing rather than following fashion) into the Renaissance, when it went mainstream for the first time in different, rather contradictory contexts: at the (very Catholic) Spanish court, where it came to symbolise serenity and sobriety, and among the members of the new Protestant creed, where it came to mean virtue and renouncing of vanity. Both dressed black from head to toe, if from different motivations. Both intellectuals and the new, rising merchant class favour black, to distinguish themselves form courtiers and peasants (below Thomas Cromwell, his fur collar and gold ring hint not-so-subtly that black does not have to be humble at all).

Richly and extensively sourced and illustrated, Men in Black is actually a cultural history of the colour black in Europe in the last 600 years or so. John Harvey looks at Chaucer, Shakespeare, Ruskin and quite extensively at Dickens, and illustrates his findings with a beautiful collection of images, mostly portraits, but also genre scenes and book illustrations. Othello and Dickens´s Victorian gentleman are followed by twentieth-century wearers of black, who are at least as contradictory as their Renaissance counterparts: Fascist organisations (called Blackshirts for a reason) prefer black (or similar dark colours), but also do countercultures, where the lack of colour, symbolised by black, becomes the essence of rebellion (Marlon Brando in the photo below, illustrates this very well).

_-_Volga_Boatmen_(1870-1873).jpg)